Dynamic linking on iOS

This is a repost of an article I published on the Realmac Software blog.

iOS is often criticized for not supporting dynamic libraries. While you might agree or disagree, it is interesting to think about why it is so and how this rule is eventually enforced. In this post we will see what these libraries are, how they come in practice, how they would work if they were fully supported on iOS and what makes it impossible to ship one in your iOS application.

Library linking

Applications are very rarely built as one big monolithic executable but are rather constructed by assembling various blocks usually called libraries. From a practical perspective, a library can be thought as an agglomerate of executable code along with some public headers and resources conveniently packaged to be linked into and consumed by an application.

While this general definition fits for most library types, there is one area where they diverge: linking. Based on this distinction, there are two families of libraries: static and dynamic libraries. I will quickly summarise the differences between the two, however, if you want to know more about the topic, I recommend reading the Dynamic Library Programming Topics guide on Apple’s website.

Static library

A static library can be thought of as an archive of object files. When linking such a library into an application, the static linker will collect the object files from the library and package them along with the application object code into one single executable file. This means that the size of the application executable file will grow with the number of libraries added. Also, when the application launches, the application code (which includes the library code) will be loaded all at once into the program’s address space.

Dynamic library

Dynamic libraries allow an application to load code into its address space when it’s actually needed. This can be either at launch time or at runtime. Dynamic libraries are not part of the application executable file.

When an application is launched, the application’s code is first loaded into the address space of the process. The dynamic loader – usually dyld on Apple’s platforms – takes control of the process and loads the dependent libraries. This involves resolving their location on the file system based on their install name, and then resolving the undefined external symbols needed by the application. The dynamic loader will also load additional libraries at runtime, as they are requested.

Framework

In the Apple world, a Framework is a bundle or package containing a dynamic library, header files and resources. Frameworks are a very neat way to group related resources together, provide an executable along with the public headers in one package that is easy to install.

It is important to note that while a framework would need to contain a dynamic library, one could quite easily create a static framework for iOS. I won’t go into details about this here but I highly recommend reading “iPhone Framework Support - Shipping Libraries” and “iOS Static Libraries Are, Like, Really Bad, And Stuff” by Landon Fuller.

Dynamic libraries on iOS

So, is it true that dynamic libraries cannot be used on iOS? Well, it is actually a bit of a misconception. Every Apple framework that you link into your application contains a dynamic shared library. Can you imagine what the size of the executable would be if you had to statically link UIKit and other frameworks into every single application?

As a matter of fact, dynamic libraries are wildly used on iOS. When your code in applicationDidFinishLaunching: starts executing, dyld has already loaded over 150 libraries!

It would be neat if we could find out which libraries are being loaded while the application is running. Luckily dyld offers some hooks for an application to be notified when an image is added or removed. Let’s create a LLImageLogger class and set some callback functions when the class loads. Let’s go through the implementation of this class. You can find the code on GitHub if you want to run it; it comes with a couple of iOS and OS X sample applications.

Logging loaded dynamic libraries

mach-o/dyld.h declares two very useful functions: _dyld_register_func_for_add_image and _dyld_register_func_for_remove_image. These functions are documented as follows:

The following functions allow you to install callbacks which will be called by dyld whenever an image is loaded or unloaded. During a call to

_dyld_register_func_for_add_image()the callback func is called for every existing image. Later, it is called as each new image is loaded and bound (but initializers not yet run). The callback registered with_dyld_register_func_for_remove_image()is called after any terminators in an image are run and before the image is un-memory-mapped.

We can easily add a couple of callbacks when our class loads.

#import <mach-o/dyld.h>

@implementation LLImageLogger

+ (void)load

{

_dyld_register_func_for_add_image(&image_added);

_dyld_register_func_for_remove_image(&image_removed);

}

@end

We now need to implement both functions. Note that the signature of the callback function is as follows:

void callback_function(const struct mach_header *mh, intptr_t vmaddr_slide);

Ideally, we will want to log some info about the loaded image to the console. The most familiar way will be to try and mimic the format of a crash report. A crash report usually has a list of images that were loaded when the program crashed. The information for each image contains the executable path, the base address, the executable text section size (or the end address) and the image UUID. This information is very useful when it comes to symbolicate a crash report.

0x2fd23000 - 0x2ff0dfff Foundation armv7s <b75ca4f9d9b739ef9b16e482db277849> /System/Library/Frameworks/Foundation.framework/Foundation

0x31c2c000 - 0x3239ffff UIKit armv7s <f725ad0982673286911bff834295ec99> /System/Library/Frameworks/UIKit.framework/UIKit

Since the callback functions are passed a pointer to the Mach-O header as first argument it should be fairly easy to retrieve this info. Let’s implement both callback functions and simply call into a common function with an extra argument determining whether the image was added or removed.

#import <mach-o/loader.h>

static void image_added(const struct mach_header *mh, intptr_t slide)

{

_print_image(mh, true);

}

static void image_removed(const struct mach_header *mh, intptr_t slide)

{

_print_image(mh, false);

}

We will now look at implementing the _print_image function. Most of the info about the Mach-O header can be retrieved by means of a function defined in dlfcn.h: dladdr. By passing the pointer to the Mach-O header and a reference to a Dl_info struct we can retrieve some key information about the image. The Dl_info struct contains the following members:

typedef struct dl_info {

const char *dli_fname; /* Pathname of shared object */

void *dli_fbase; /* Base address of shared object */

const char *dli_sname; /* Name of nearest symbol */

void *dli_saddr; /* Address of nearest symbol */

} Dl_info;

Keeping this in mind, we can now take a look at the implementation of the _print_image function:

#import <dlfcn.h>

static void _print_image(const struct mach_header *mh, bool added)

{

Dl_info image_info;

int result = dladdr(mh, &image_info);

if (result == 0) {

printf("Could not print info for mach_header: %p\n\n", mh);

return;

}

const char *image_name = image_info.dli_fname;

const intptr_t image_base_address = (intptr_t)image_info.dli_fbase;

const uint64_t image_text_size = _image_text_segment_size(mh);

char image_uuid[37];

const uuid_t *image_uuid_bytes = _image_retrieve_uuid(mh);

uuid_unparse(*image_uuid_bytes, image_uuid);

const char *log = added ? "Added" : "Removed";

printf("%s: 0x%02lx (0x%02llx) %s <%s>\n\n", log, image_base_address, image_text_size, image_name, image_uuid);

}

As you can see, it’s nothing too fancy. We start by retrieving the Dl_info struct for the Mach-O header and then populate the required information. While the base address and image path are directly available in the struct, we will have to manually retrieve the image text segment size and the image UUID from the binary. This is exactly what the _image_retrieve_uuid and _image_text_segment_size do.

For these two functions, we will have to walk the Mach-O file load commands. I recommend reading the OS X ABI Mach-O File Format Reference from Apple for a good overview of the Mach-O file format. In a nutshell, a Mach-O file is composed of a header, a series of load commands and data composed of multiple segments. Information about the segments (such as their offset and size) is available in the segment load commands.

We will start with creating a visitor function that we’ll be able to reuse across both functions.

static uint32_t _image_header_size(const struct mach_header *mh)

{

bool is_header_64_bit = (mh->magic == MH_MAGIC_64 || mh->magic == MH_CIGAM_64);

return (is_header_64_bit ? sizeof(struct mach_header_64) : sizeof(struct mach_header));

}

static void _image_visit_load_commands(const struct mach_header *mh, void (^visitor)(struct load_command *lc, bool *stop))

{

assert(visitor != NULL);

uintptr_t lc_cursor = (uintptr_t)mh + _image_header_size(mh);

for (uint32_t idx = 0; idx < mh->ncmds; idx++) {

struct load_command *lc = (struct load_command *)lc_cursor;

bool stop = false;

visitor(lc, &stop);

if (stop) {

return;

}

lc_cursor += lc->cmdsize;

}

}

This functions takes a pointer to a Mach-O header and a visitor block. It then invokes the block for each load command it finds. Note the helper function to retrieve the size of the Mach-O header which we’ll need in order to find the address of the first load command. This is due to the fact that there are two different structs for the Mach-O header: mach_header and mach_header_64, based on whether the architecture is 64-bit or not. Luckily the first field in the header struct is a magic number giving information about the architecture.

With this helper function written we should be able to implement the _image_retrieve_uuid and _image_text_segment_size functions.

static const uuid_t *_image_retrieve_uuid(const struct mach_header *mh)

{

__block const struct uuid_command *uuid_cmd = NULL;

_image_visit_load_commands(mh, ^ (struct load_command *lc, bool *stop) {

if (lc->cmdsize == 0) {

return;

}

if (lc->cmd == LC_UUID) {

uuid_cmd = (const struct uuid_command *)lc;

*stop = true;

}

});

if (uuid_cmd == NULL) {

return NULL;

}

return &uuid_cmd->uuid;

}

This function is very simple too. It looks for the LC_UUID command and retrieves the uuid_t once it finds it. The _print_image will then take care of transforming the uuid_t into a string by mean of uuid_unparse.

Finally, here is the implementation of the _image_text_segment_size function:

static uint64_t _image_text_segment_size(const struct mach_header *mh)

{

static const char *text_segment_name = "__TEXT";

__block uint64_t text_size = 0;

_image_visit_load_commands(mh, ^ (struct load_command *lc, bool *stop) {

if (lc->cmdsize == 0) {

return;

}

if (lc->cmd == LC_SEGMENT) {

struct segment_command *seg_cmd = (struct segment_command *)lc;

if (strcmp(seg_cmd->segname, text_segment_name) == 0) {

text_size = seg_cmd->vmsize;

*stop = true;

return;

}

}

if (lc->cmd == LC_SEGMENT_64) {

struct segment_command_64 *seg_cmd = (struct segment_command_64 *)lc;

if (strcmp(seg_cmd->segname, text_segment_name) == 0) {

text_size = seg_cmd->vmsize;

*stop = true;

return;

}

}

});

return text_size;

}

Nothing too fancy here either. The visitor block simply looks for segment commands (LC_SEGMENT on 32-bit and LC_SEGMENT_64 on 64-bit) and checks whether the current load segment is the __TEXT segment. If it is, it then retrieves the vmsize and returns it as the text size.

By running the application on the iOS Simulator, the following is logged:

Added: 0x10000b000 (0x2a8000) /Applications/Xcode.app/Contents/Developer/Platforms/iPhoneSimulator.platform/Developer/SDKs/iPhoneSimulator7.1.sdk/System/Library/Frameworks/Foundation.framework/Foundation <C299A741-488A-3656-A410-A7BE59926B13>

…

Added: 0x110527000 (0x385000) /Applications/Xcode.app/Contents/Developer/Platforms/iPhoneSimulator.platform/Developer/SDKs/iPhoneSimulator7.1.sdk/System/Library/Frameworks/AudioToolbox.framework/AudioToolbox <57B61C9C-8767-3B3A-BBB5-8768A682383A>

There are 147 images loaded when launching a very simple iOS application!

We thus showed that dynamic libraries were indeed loaded in our iOS application. So what about the dynamic libraries are not supported on iOS argument? Well, let’s try and build one and see what happens!

Building a dynamic library on iOS

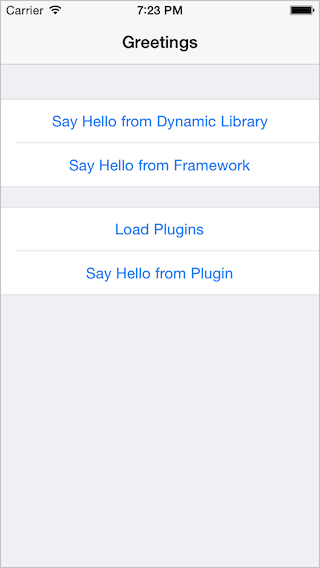

In the following section, we will attempt to build three products that are common on the Mac but not supported on iOS:

- A simple dynamic library linked by the application

- A framework (a legit one, containing a dynamic shared library)

- A plugin (i.e. a bundle containing an executable, not packaged with the application but loaded at runtime)

As usual, you can find the sample project on GitHub.

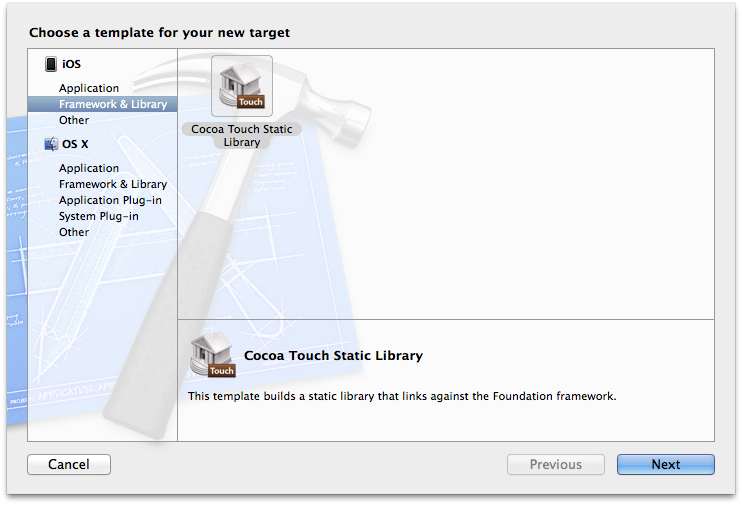

Dynamic library on iOS

Let’s start by creating a dynamic library target for our iOS application. Oh wait…

Xcode (logically) doesn’t provide a configuration template for a dynamic library on iOS. Luckily we can select a library from the OS X section and simply change the deployment target and architectures to build in the Build Settings.

If you do this and create your library however, you will get an error when trying to build

Check dependencies:

Target specifies product type 'com.apple.product-type.library.dynamic', but there's no such product type for the 'iphoneos' platform

In order to fix this you will have to update the Xcode Specifications for the PackageTypes and ProductTypes for both the iPhone Simulator and the iPhone OS. Instructions on how to do this can be found here.

With this in mind, we can create a simple class, add a sayHello method which implementation simply creates and shows an alert view and add the class to the library target. We can then add the library to the Link Binary with Library build phase for the application. Finally we have to add a Copy build phase and copy the dynamic library to the application bundle. See the sample project for more info on how to set this up.

We can then import the library header (we marked it as public and made sure that it was in the Header Search Paths), instantiate an object and call the sayHello method. If you run the application in the iOS simulator you should see the alert view popping up. Wait, did we just load and run some code from a dynamic library and iOS? Looks like it… (Don’t attempt to run this on a device just yet, we’ll discuss it later).

Framework on iOS

Now that we‘ve seen that we can load and use a dynamic library, it would be awesome if we could just build a framework around it so that we can pack additional resource easily and don’t have to worry about header search paths.

Similarly to the dynamic library case we can create a framework by using the Mac template and change the deployment target and build architectures. We will also create a plist that will be copied as a resource in the framework bundle. We will load the alert view message from the plist, mostly to demonstrate that resource loading works fine from the framework bundle.

Making sure that the header has been marked as public, we can then simply import the framework in the application:

#import "Framework/Framework.h"

Finally, we can instantiate the class and call the method. We should see the alert which message has been loaded from a resource in the framework bundle. It works!

Plugin on iOS

This last one is the most interesting. Applications on the Mac can be extended in a very neat way by supporting plugins. In simple words, a plugin, just like a framework, is a bundle containing an executable and some resources. The plugin declares its principal class in its Info.plist. Usually the principal class is a subclass of an abstract class defined by the application or conforms to a protocol made available by the application.

In order to load the plugin at runtime, the host application will instantiate an NSBundle instance for the plugin location, preflight the bundle to check that it can indeed be loaded and eventually load it. Loading a bundle will dynamically loads the bundle’s executable code into the running program. Once the bundle has been loaded the host application can retrieve the principal class and instantiate it.

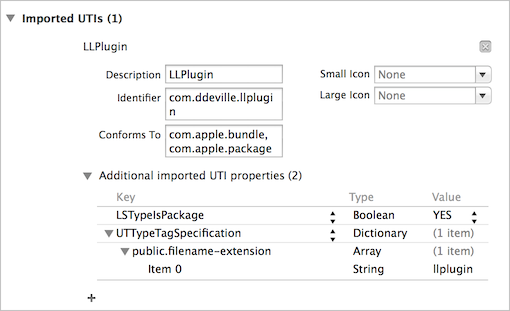

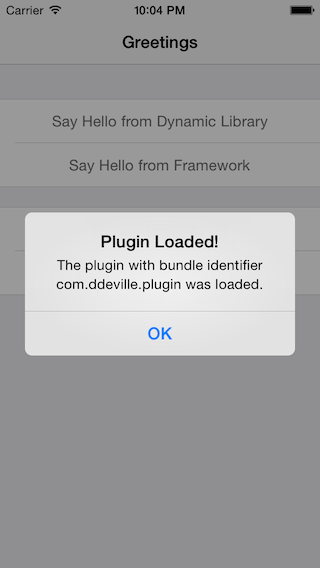

So let’s try and build this for iOS. We can create a new target by using the Bundle template. After changing the deployment target and build architecture we create a new class and set it as the NSPrincipalClass in the Info.plist. Similarly to the framework we will create a plist and load the alert message from it at runtime. We also need to make sure that we specify a custom extension for the bundle – here we will use llplugin.

We can then build the plugin and keep the product somewhere safe. We will then copy it in the Documents directory of the iOS application (you can find the application under ~/Library/Application Support/iPhone Simulator/7.1-64/Applications. You might have to change the SDK version based on your platform)

In the host application, we will need to add an imported UTI for the plugin so that we can recognize its file type.

With the plugin type declared we can now iterate through the contents of the Documents directory and look for plugins, checking conformance to the type for every found item by using UTTypeConformsTo. For each found plugin we can then load the bundle, retrieve the principal class and instantiate it.

- (void)_loadPluginAtLocation:(NSURL *)pluginLocation

{

NSBundle *plugin = [[NSBundle alloc] initWithURL:pluginLocation];

NSError *preflightError = nil;

BOOL preflight = [plugin preflightAndReturnError:&preflightError];

if (!preflight) {

return;

}

BOOL loaded = [plugin load];

if (!loaded) {

return;

}

Class pluginClass = [plugin principalClass];

if (pluginClass == nil) {

return;

}

id pluginInstance = [[pluginClass alloc] init];

if (![pluginInstance respondsToSelector:@selector(sayHello)]) {

return;

}

[pluginInstance sayHello];

}

If we copy our built plugin in the Documents directory and run the application we should see an alert saying hello. By using the LLImageLogger we can also note that the LLPlugin image is only loaded by the time -[NSBundle load] is called.

We were able to link and load a dynamic library and a framework in an iOS application running in the simulator. We were also able to dynamically load a plugin at runtime and run some of its code, also in the simulator. As you might have guessed there is a catch. So far we’ve only been running our application in the simulator. What happens if we run it on a device?

What about running on the device?

If you attempt to build for running on an actual device Xcode will likely complain that the libraries need to be codesigned. Even if you codesign them you will run into problems when launching your application (this might not happened while you’re debugging the application due to the fact that applications behave slightly differently while being debugged on a device on which Developer Mode has been enabled).

Linked dynamic library

When attempting to run the application containing the dynamic library on the device Xcode will prompt you that the dynamic library has to be code signed. We can simply sign it using the same code sign identity as the application’s. When running it on the device however you will get the following message during dyld bootstrap and the program will be halted.

dyld: Library not loaded: @executable_path/Library.dylib Referenced from: /var/mobile/Applications/DC816A37-F0D4-4F72-9EC8-A642A03C0ABC/Dynamic.app/Dynamic Reason: no suitable image found. Did find: /var/mobile/Applications/DC816A37-F0D4-4F72-9EC8-A642A03C0ABC/Dynamic.app/Library.dylib: code signature invalid for '/var/mobile/Applications/DC816A37-F0D4-4F72-9EC8-A642A03C0ABC/Dynamic.app/Library.dylib'

So it seems like dyld is denying the load of the library based on the invalidity of its signature.

This happens during the program load, precisely during the dyld bootstrapping. But what about loading a plugin bundle at runtime?

Plugin loaded at runtime

Let’s see what happens when loading our plugin. When attempting to load the plugin at runtime the application will likely crash with the following backtrace:

Exception Type: EXC_CRASH (SIGKILL - CODESIGNING)

Thread 0 Crashed:

0 dyld 0x2be50c40 ImageLoaderMachO::crashIfInvalidCodeSignature + 72

1 dyld 0x2be5557a ImageLoaderMachOCompressed::instantiateFromFile + 286

2 dyld 0x2be50b44 ImageLoaderMachO::instantiateFromFile + 204

3 dyld 0x2be48036 dyld::loadPhase6 + 390

4 dyld 0x2be4b9b0 dyld::loadPhase5stat + 296

5 dyld 0x2be4b7c6 dyld::loadPhase5 + 390

6 dyld 0x2be4b61c dyld::loadPhase4 + 128

7 dyld 0x2be4b53c dyld::loadPhase3 + 1000

8 dyld 0x2be4afd0 dyld::loadPhase1 + 108

9 dyld 0x2be47e0a dyld::loadPhase0 + 162

10 dyld 0x2be47bb4 dyld::load + 208

11 dyld 0x2be4d1b2 dlopen + 790

12 libdyld.dylib 0x3a09a78a dlopen + 46

13 CoreFoundation 0x2f392754 _CFBundleDlfcnLoadBundle + 120

14 CoreFoundation 0x2f3925a4 _CFBundleLoadExecutableAndReturnError + 328

15 Foundation 0x2fd7f674 -[NSBundle loadAndReturnError:] + 532

16 Foundation 0x2fd8f51e -[NSBundle load] + 18

17 Dynamic 0x000f64be -[LLViewController _loadPluginAtLocation:]

The application is killed while dyld is attempting to load the bundle. We can only see the userland side of things here but the function at the top frame of the stack should give us a good idea: ImageLoaderMachO::crashIfInvalidCodeSignature. It is worth noting that the plugin we copied into the Documents folder was not code signed. Before attempting to codesign it, let’s quickly analyze what leads to the program being killed when loading the plugin.

In User Space

Luckily, dyld is open-source so we can have a quick look at the implementation of the ImageLoaderMachO::crashIfInvalidCodeSignature function to try and figure out what happened. The file in question is ImageLoaderMachO.cpp and its implementation is pretty simple:

int ImageLoaderMachO::crashIfInvalidCodeSignature()

{

// Now that segments are mapped in, try reading from first executable segment

// If code signing is enabled the kernel will validate the code signature

// when paging in, and kill the process if invalid

for (unsigned int i = 0; i < fSegmentsCount; ++i) {

if ((segFileOffset(i) == 0) && (segFileSize(i) != 0)) {

// return read value to ensure compiler does not optimize away load

int* p = (int*)segActualLoadAddress(i);

return *p;

}

}

return 0;

}

This is a pretty naïve (but effective!) way to check the signature and crash if it’s invalid or inexistent: attempt to read from the first executable segment in the executable letting the kernel kill the process should it discover that the code signature cannot be validated when paging in.

In the kernel

The kernel itself is also open-source so we can take a look at it and try and figure out where and how the code signature is verified. I should point out here that reading kernel code is slightly out of my confort zone and I found some great help in Charlie Miller’s SyScan’11 talk Don’t Hassle The Hoff: Breaking iOS Code Signing and book iOS Hacker’s Handbook.

While this is a fascinating subject it could get quite lengthy so I won’t go into details here.

In a nutshell, when codesigned, a Mach-O executable will contain a LC_CODE_SIGNATURE load command referencing a code signature segment in the binary. We can verify it with otool on a signed binary:

> otool -l Plugin.llplugin/Plugin

…

Load command 17

cmd LC_CODE_SIGNATURE

cmdsize 16

dataoff 9968

datasize 9616

…

In the kernel, the Mach-O file is loaded and parsed in the parse_machfile function and the signature is loaded in load_code_signature, both in mach_loader.c. Eventually the signature is checked and its validity is stored inside the csflags member of the kernel’s proc struct for the process.

Later on, whenever a page fault occurs the vm_fault function in vm_fault.c is called. During the page fault the signature is validated if necessary. The signature will need to be validated if the page is mapped in user space, if the page belongs to a code-signed object, if the page will be writable or simply if it has not previously been validated. Validation happens in the vm_page_validate_cs function inside vm_fault.c (the validation process and how it is enforced continually and not only at load time is interesting, see Charlie Miller’s book for more details).

If for some reason the page cannot be validated, the kernel checks whether the CS_KILL flag has been set and kills the process if necessary. There is a major distinction between iOS and OS X regarding this flag. All iOS processes have this flag set whereas on OS X, although code signing is checked it is not set and thus not enforced.

In our case we can safely assume that the (missing) code signature couldn’t be verified leading to the kernel killing the process.

Situation when code signing the plugin

It was pretty obvious to see that dyld refused to load the plugin executable due to its lack of code signature. We can change this.

codesign --sign "iPhone Developer" --force --verbose=4 Plugin.llplugin

When code signing the plugin bundle by using the codesign Terminal utility dyld correctly loads the file at runtime and the plugin code executes correctly, even on the device.

We thus have no problem dynamically loading an external plugin bundle containing executable code at runtime, even on a device. There is a big caveat to this: we were able to sign the plugin with our Developer certificate given that our device is present in the provisioning profile. For this scenario to happen with a shipped application, the plugin would need to be signed by Apple just like any application submitted to the App Store.

While I don’t see Apple supporting (signed and approved) plugins on iOS anytime soon, I think the dynamic library restrictions could potentially be loosened. By requiring any included executable to be signed with the same certificate as the main application – just like for the Mac App Store – Apple could review them as part of the App Store approval process. Dynamic libraries (in particular when bundled in a framework) would make library distribution so much cleaner and would obsolete the multitude of hacks we have created in order to simply share code.

Conclusion

- Dynamic libraries signed by Apple can be (and are!) loaded by an iOS application

- A simple iOS application loads over 150 dynamic libraries on launch

- Xcode doesn’t support creating dynamic libraries, frameworks or plugins on iOS but it is very easy to work around this

- If code signing were not a thing we could load dynamic libraries, frameworks and load plugins at runtime on iOS just like we do on the Mac

- In practice, the kernel will kill any application that attempts to load a dynamic library that is not signed or which signature cannot be validated

- A shipping dynamic library would need to be signed by Apple with the same certificate as the one used for App Store applications

- Last but not least, the App Store policies don’t allow dynamic libraries and even if it were technically possible it wouldn’t pass App Store validation

You can find the source code for the Image Logger and Dynamic iOS projects on GitHub.

If you have any question, you can find me on Twitter.